-

August 01, 2013

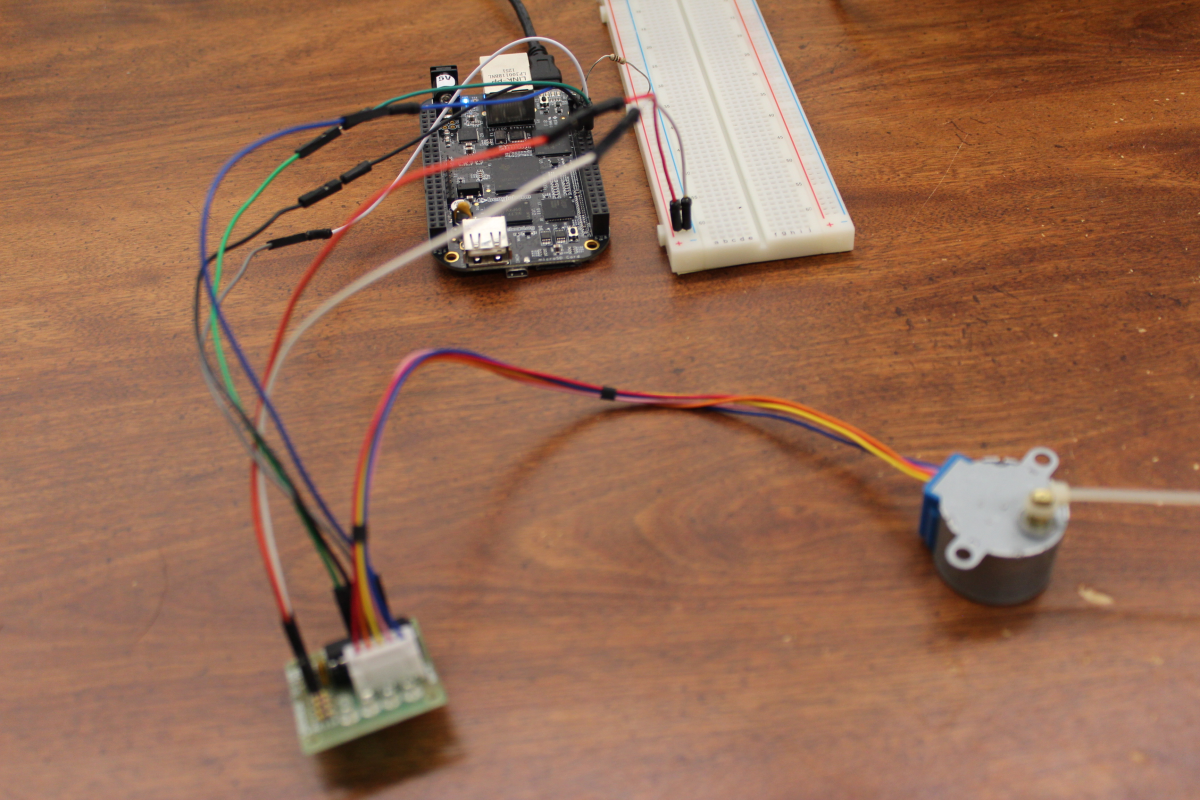

Stepper motor control with the BeagleBone Black and Python

The BeagleBone Black (BBB) is a $45 credit-card-sized computer that runs embedded Linux. I recently purchased a BBB along with an $8 4-phase stepper motor and driver to start playing around with slightly “closer-to-the-metal” motion control.

My first objective with the BBB was to simply get the stepper to move, and for this I started using the included Cloud9 IDE and BoneScript library. After a while messing around and learning a little JavaScript, along with some help from my programmer brother Tom, the stepper was moving in one direction using wave drive logic. However, the code felt awkward. I decided I’d rather use Python, since I’m a lot more comfortable with it, so I went out in search of Python packages or modules for working with the BeagleBone’s general purpose I/O (GPIO) pins. I found two: Alexander Hiam’s PyBBIO and Adafruit’s Adafruit_BBIO. Adafruit_BBIO seemed to be more frequently maintained and better documented, so I installed it on the BeagleBone per their instructions, which was pretty quick and painless.

Stepper motor wired up to the BeagleBone Black. Next, I wrote a small, simple python module, BBpystepper, with a

Stepperclass for creating and working with a stepper control object. Currently the control uses full-step drive logic, with wave drive available by changingStepper.drivemode. I may add half-stepping in the future, but for now full-stepping gets the job done.Usage

After installing Adafruit_BBIO and BBpystepper on the BeagleBone, the module can be imported into a Python script or run from a Python interpreter. For example:

>>> from bbpystepper import Stepper >>> mystepper = Stepper() >>> mystepper.rotate(180, 10) # Rotates motor 180 degrees at 10 RPM >>> mystepper.rotate(-180, 5) # Rotates motor back 180 degrees at 5 RPM >>> mystepper.angle 0.0Notes

-

By default the GPIO pins used are P8_13, P8_14, P8_15, and P8_16. These can be changed by modifying the

Stepper.pinslist. -

By default the

Stepper.steps_per_revparameter is set to 2048 to match my motor (it has a built-in gearbox). -

The code doesn’t keep track of where it ends in the sequence of pins. It simply sets all pins low after a move. This means there could be some additional error in the

Stepper.anglevariable if the amount of steps moved is not divisible by 4.

Final Thoughts

As mentioned previously, half-stepping would be a nice future add-on, along with a more accurate way of keeping track of the motor shaft angle. Another logical next step would be to use one of the BBB’s Programmable Real-Time Units (PRUs) to control the timing more precisely, therefore improving speed accuracy and allowing synchronization with other processes, e.g. data acquisition. However, for now this simple method gets the job done.

-

-

July 23, 2013

Diesel Explorer: Choosing a chassis

Having settled in on the Cummins B3.3 for an engine, the next step was to choose a vehicle to put it in. I had some rough requirements in mind:

- Seating capacity: At least 4 people

- Air conditioning and decent acoustics/sound system

- 4-wheel drive

Since the original inspiration for the project was a Cummins B3.3 in a Jeep Wrangler (YJ), that was an obvious candidate, but I also had an affinity for and experience with Ford body styles and interiors. The decision came down to two potential chassis: Wrangler vs. Explorer. Both satisfied the basic requirement above, but there were some more criteria to consider—fitment, noise and comfort, emissions, initial cost, and fuel economy.

Fitment

An obvious requirement was that the engine fit inside the vehicle’s engine bay. This contest goes to the Wrangler. The engine bay is huge, and the hood opens very wide. With the Explorer, a body lift would most likely be necessary.

Winner: Wrangler

Noise/acoustics and overall comfort

The fun and excitement of the Jeep’s removable top comes along with a noisy ride, and poor acoustics. For me, the Explorer’s acoustics and comfort were worth the somewhat less hip styling. Electric windows and locks were icing on the cake.

Winner: Explorer

Initial cost

On the used market, Wranglers fetch about 2–3 times the amount Explorers do. Spending less on a chassis would save more for the engine, giving the Explorer the edge.

Winner: Explorer

Emissions

Since this vehicle would likely throw many error codes with an OBD-II computer, it was important to find a vehicle that was OBD-I. The TJ body style is not available in the OBD-I years, while the 2nd generation Explorer body style was just introduced in 1995, barely making the cutoff. The Explorer body style and interior both beat the YJ, as discussed above, so the Explorer gets the nod here.

Winner: Explorer

Fuel economy

The most important metric—and the main goal of the project—was to achieve high fuel efficiency. Thus, this metric would likely decide the contest. Properties for the two vehicles are tabulated below. On one hand, the Wrangler is lighter than the Explorer, requiring less energy to get up to speed. However, the Wrangler is also less aerodynamic, consuming more energy while cruising. To compare the two, a typical driving scheme was devised, for which rough estimates for fuel consumption were calculated. This driving scheme included

- Accelerating 0–40 mph in 10 seconds

- Cruising at 40 mph for 5 miles

Explorer Wrangler Mass (kg) 1806 [1] 1331 [2] Drag coefficient 0.43 [3] 0.55 [3] Frontal area ($\text{m}^2 $) 2.3 2.3 Calculating fuel consumption during cruising

This was the easy part. Neglecting friction in the tires and drivetrain—which would be more or less equivalent between both vehicles—energy consumption during cruising can be estimated by integrating the drag force over the distance traveled.

Drag force is estimated using the formula \(F_D = \frac{1}{2}\rho A_f C_D V^2,\)

where $ \rho $ is the density of air, $ A_f $ is the vehicle’s frontal area (approximately equal for both Explorer and Wrangler), $ C_D $ is the vehicle’s drag coefficient, and $ V $ is the cruising speed. Since speed is constant, the integration simplifies to multiplication, giving (in Nm)

\[E_{\mathrm{cruise}} = 3,550,673 C_D.\]Calculating fuel consumption during acceleration

Calculating the energy required during acceleration included consideration of both drag and inertial forces. Since drag is not constant during acceleration, we will use a more general method and integrate the varying power over the acceleration time, which is simply the force multiplied by velocity, or

\[E_{\mathrm{acc}} = \int_0^{10} \left( F_D V + maV \right) \, \mathrm{d}t.\]Integrating the constant acceleration gives the vehicle speed as a function of time, i.e.,

\[V(t) = \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} = 1.79 t.\]Boiling this all down and substituting all but the variables that differ between the vehicles, we obtain

\[E_{\mathrm{acc}} = 19,787 C_D + 160.2m.\]The table below summarizes the results for both vehicles. As you can see, these estimates show the Explorer consuming 16% less energy than the Wrangler, making it a better choice with regards to fuel economy.

Explorer Wrangler Energy consumed during cruising (Nm) $ 1.53 \times 10^6 $ $ 1.95 \times 10^6 $ Energy consumed during acceleration (Nm) $ 2.98 \times 10^5 $ $ 2.24 \times 10^5 $ Total energy consumed (Nm) $ 1.83 \times 10^6 $ $ 2.17 \times 10^6 $ Winner: Explorer

Conclusions

Obviously, since this post is in a series about a diesel Explorer, you can guess which chassis won out in the end. The Wrangler is a cool design for sure, but the Explorer’s acoustics, comfort, and most importantly aerodynamics made it my choice.

References

[1] https://www.edmunds.com/ford/explorer/1995/features-specs.html

[2] https://www.edmunds.com/jeep/wrangler/1995/features-specs.html

[3] https://ecomodder.com/wiki/index.php/Vehicle_Coefficient_of_Drag_List