Continuous Reproducibility: How DevOps principles could improve the speed and quality of scientific discovery

In the 21st century, the Agile and DevOps movements revolutionized software development, reducing waste, improving quality, enhancing innovation, and ultimately increasing the speed at which software products were brought into the world. At the same time, the pace of scientific innovation appears to have slowed [1], with many findings failing to replicate (validated in an end-to-end sense by reacquiring and reanalyzing raw data) or even reproduce (obtaining the same results by rerunning the same computational processes on the same input data). Science already borrows much from the software world in terms of tooling and best practices, which makes sense since nearly every scientific study involves computation, but there are still more yet to cross over.

Here I will focus on one set of practices in particular: those of Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CI/CD). There has been some discussion about adapting these under the name Continuous Analysis [2], though since the concept extends beyond analysis and into generating other artifacts like figures and publications, here I will use the term Continuous Reproducibility (CR).

CI means that valuable changes to code are incorporated into a single source of truth, or “main branch,” as quickly as possible, resulting in a continuous flow of small changes rather than in larger, less frequent batches. CD means that these changes are accessible to the users as soon as possible, e.g., daily instead of quarterly or annual “big bang” releases.

CI/CD best practices ensure that software remains working and available while evolving, allowing the developers to feel safe and confident about their modifications. Similarly, CR would ensure the research project remains reproducible—its output artifacts like datasets, figures, slideshows, and publications, remain consistent with input data and process definitions—hypothetically allowing researchers to make changes more quickly and in smaller batches without fear of breaking anything.

But CI and CD did not crop up in isolation. They arose as part of a larger wave of changes in software development philosophy.

In its less mature era, software was built using the traditional waterfall project management methodology. This approach broke projects down into distinct phases or “stage gates,” e.g., market research, requirements gathering, design, implementation, testing, deployment, which were intended to be done in a linear sequence, each taking weeks or months to finish. The industry eventually realized that this only works well for projects with low uncertainty, i.e., those where the true requirements can easily be defined up front and no new knowledge is uncovered between phases. These situations are of course rare in both product development and science.

These days, in the software product world, all of the phases are happening continuously and in parallel. The best teams are deploying new code many times per day, because generally, the more iterations, the more successful the product.

But it’s only possible to do many iterations if cycle times can be shortened. In the old waterfall framework, full cycle times were on the order of months or even years. Large batches of work were transferred between different teams in the form of documentation—a heavy and sometimes ineffective communication mechanism. Further, the processes to test and release software were manual, which meant they could be tedious, expensive, and/or error prone, providing an incentive to do them less often.

One strategy that helped reduce iteration cycle time was to reduce communication overhead by combining development and operations teams (hence “DevOps”). This allowed individuals to simply talk to each other instead of handing off formal documentation. Another crucial tactic was the automation of test and release processes with CI/CD pipelines. Combined, these made it practical to incorporate fewer changes in each iteration, which helped to avoid mistakes and deliver value to users more quickly—a critical priority in a competitive marketplace.

I’ve heard DevOps described as “turning collaborators into contributors.” To achieve this, it’s important to minimize the amount of effort required to get set up to start working on a project. Since automated CI/CD pipelines typically run on fresh or mostly stateless virtual machines, setting up a development/test environment needs to be automated, e.g., with the help of containers and/or package managers. These pipelines then serve as continuously tested documentation, which can be much more reliable than a list of steps written in a README.

So how does this relate to research projects, and are there potential efficiency gains to be had if similar practices were to be adopted?

In research projects we certainly might find ourselves thinking in a waterfall mindset, with a natural inclination to work in distinct, siloed phases, e.g., planning, data collection, data analysis, figure generation, writing, peer review. But is a scientific study really best modeled as a waterfall process? Do we never, for example, need to return to data analysis after starting the writing or peer review?

Instead, we could think of a research project as one continuous iterative process. Writing can be done the entire time in small chunks. For example, we can start writing the introduction to our first paper and thesis from day one, as we do our literature review. The methods section of a paper can be written as part of planning an experiment, and updated with important details while carrying it out. Data analysis and visualization code can be written and tested before data is collected, then run during data collection as a quality check. Instead of thinking of the project as a set of decoupled sub-projects, each a big step done one after the other, we could think of the whole thing as one unit that evolves in small steps.

Similar to how software teams work, where an automated CD pipeline will build all artifacts, such as compiled binaries or minified web application code, and make them available to the users, we can build and deliver all of our research project artifacts each iteration with an automated pipeline, keeping them continuously reproducible. (Note that in this case “deliver” could mean to our internal team if we haven’t yet submitted to a journal.)

In any case, the correlation between more iterations and better outcomes appears to be mostly universal for all kinds of endeavors, so at the very least, we should look for behaviors that are hurting research project iteration cycle time. Here are a few DevOps-related ones I can think of:

| Problem or task | Slower, more error-prone solution ❌ | Better solution ✅ |

|---|---|---|

| Ensuring everyone on the team has access to the latest version of a file as soon as it is updated, and making them aware of the difference from the last version. | Send an email to the whole team with the file and change summary attached every time a file changes. | Use a single shared version-controlled repository for all files and treat this as the one source of truth. |

| Updating all necessary figures and publications after changing data processing algorithms. | Run downstream processes manually as needed, determining the sequence on a case-by-case basis. | Use a pipeline system that tracks inputs and outputs and uses caching to skip unnecessary expensive steps, and can run them all with a single command. |

| Ensuring the figures in a manuscript draft are up-to-date after changing a plotting script. | Manually copy/import the figure files from an analytics app into a writing app. | Edit the plotting scripts and manuscript files in the same app (e.g., VS Code) and keep them in the same repository. Update both with a single command. |

| Showing the latest status of the project to all collaborators. | Manually create a new slideshow for each update. | Update a single working copy of the figures, manuscripts, and slides as the project progresses so anyone can view asynchronously. |

| Ensuring all collaborators can contribute to all aspects of the project. | Make certain tasks only able to be done by certain individuals on the team, and email each other feedback for updating these. | Use a tool that automatically manages computational environments so it’s easy for anyone to get set up and run the pipeline. Or better, run the pipeline automatically with a CI/CD service like GitHub Actions. |

What do you think? Are you encountering these sorts of context switching and communication overhead losses in your own projects? Is it worth the effort to make a project continuously reproducible? I think it is, though I’m biased, since I’ve been working on tools to make it easier (Calkit; cf. this example CI/CD workflow).

One argument you might have against against adopting CR in your project is that you do very few “outer loop” iterations. That is, you are able to effectively work in phases so, e.g., siloing the writing away from the data visualization is not slowing you down. I would argue, however, that analyzing and visualizing data concurrently while it’s being collected is a great way to catch errors, and the earlier an error is caught, the cheaper it is to fix. If the paper is set up and ready to write during data collection, important details can make their way in directly, removing a potential source of error from transcribing lab notebooks.

---

title: Outer loop(s)

---

flowchart LR

A[collect data] --> B[analyze data]

B --> C[visualize data]

C --> D[write paper]

D --> A

C --> A

D --> C

D --> B

C --> B

B --> D

B --> A

---

title: Inner loop

---

flowchart LR

A[write] --> B[run]

B --> C[review]

C --> A

Using Calkit or a similar workflow like that of showyourwork, one can work on both outer and inner loop iterations in a single interface, e.g., VS Code, reducing context switching costs.

On the other hand, maybe the important cycle time(s) are not for iterations within a given study, but at a higher level—iterations between studies themselves. However, one could argue that delivering a fully reproducible project along with a paper provides a working template for the next study, effectively reducing that “outer outer loop” cycle time.

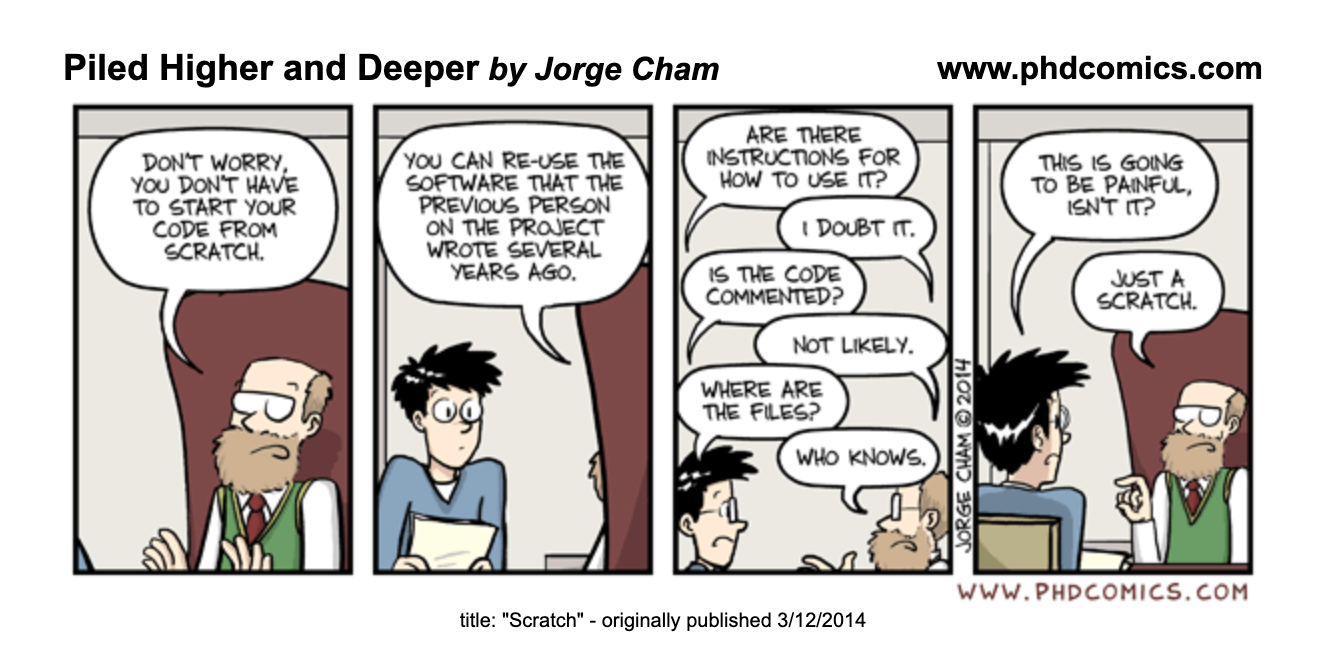

If CR practices make it easy to get set up and run a project, and again, the thing actually works, perhaps the next study can be done more quickly. At the very least, the new project owner will not need to reinvent the wheel in terms of project structure and tooling. Even if it’s just one day per study saved, imagine how that compounds over space and time. I’m sure you’ve either encountered or heard stories of grad students being handed code from their departed predecessors with no instructions on how to run it, no version history, no test suite, etc. Apparently that’s common enough to make a PhD Comic about it:

If you’re convinced of the value of Continuous Reproducibility—or just curious about it—and want help implementing CI/CD/CR practices in your lab, shoot me an email, and I’d be happy to help.

References and recommended resources

- Nicholas Bloom, Charles I Jones, John Van Reenen, and Michael Web (2020). Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find? American Economic Review. 10.1257/aer.20180338

- Brett K Beaulieu-Jones and Casey S Greene (2017). Reproducibility of computational workflows is automated using continuous analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 10.1038/nbt.3780

- Toward a Culture of Computational Reproducibility. https://youtube.com/watch?v=XjW3t-qXAiE

- There is a better way to automate and manage your (fluid) simulations. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGQlSScH97s